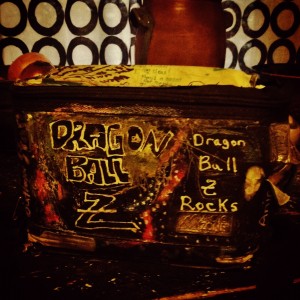

I nudge the Klingon Bird of Prey an inch or so closer to the USS Enterprise to make room for the mint condition Star Trek puzzle—still in the plastic!—and wonder if my DragonBall Z VHS tapes and action figures will fit on the same table.

It’s then, as I step back to survey the tableau, that I realize why I hadn’t lost my virginity in high school.

Sighing, I cross out the puzzle’s ten dollar price and scribble in five.

Then take stock of my parents’ liquor cabinet.

***

It’s an oddly disconcerting feeling to pull out boxes from your parents’ attic and closets, haul them onto the front lawn, and know they’re not coming back inside. It’s not a holiday, and these aren’t temporary decorations. They’re “Everything must go!”

Especially that unfortunate Easter basket cornucopia overflowing near Laura’s New Kids on the Block beach towel.

Having been empty nesters for several years, our parents decided to downsize and retire to their hobbitesque, off-grid, semi-subterranean house in the Alabama woods. It’d always been a dream of theirs, as long as Laura and I could remember. But I’d always assumed it was a distant dream, never to be writ into the landscape, only in their minds.

But now, it was real. And it was time to clean out our childhood home, box up its interior décor and ship it out to The Shire or the front porch to sell.

Once I start packing a trunk with the essentials, I loiter among the remaining books, cars, and furniture stacked hoarder-style on the porch. I step over the rope tied between the columns, the sign Dad has taped to it reading, “If you can read this, you’re in range!”

Various stages of our childhoods and their associated recollections drip off table edges and pool in massive fifty-cent piles.

Trolls with homemade haircuts. Stacks of anime books. A crumpled My So Called Life poster. And then I trip over a pile of plastic marine mammals I’d begged my parents to order.

From a science magazine.

They’d been some of my favorites.

And had made cameos in the play session that ended my childhood.

***

It’d been a hot day in the Serengeti, and plenty of creatures were hauling their dehydrated hides to the last watering hole for miles. Unbeknownst to them, though, G.I. Joes were camped along its banks. And they hadn’t eaten in days.

Tired, weak animals + famished G.I. Joes = massive carnage. Just as Ace and Chuckles attempt to ambush a dithering polar bear, the ground trembles.

An earthquake? How delightfully unintended! Especially since it’s not my doing.

But whose? Cobra looks pretty suspicious, eyeing a partially submerged seal from his dandelion perch. But it’s not Cobra.

It’s Le Sabre. My neighbor’s blue, airship-sized car.

I freeze, hoping that, like a T-Rex, Mr. Still won’t notice me as his car crawls down the gravel alley between our houses.

But he does.

And waves.

I stare. Mortified.

And that’s how my childhood ends: with a wave of a gregarious, geriatric neighbor.

He drives on, and I look back down at the mud hole and see a bunch of toys. Toys for which I’m now too old.

I’ve been spotted. Playing. Like a kid.

Sure, my parents have seen me splash around in the same mud hole on countless occasions, but they’re under parental obligation to let it go. Now, I’m exposed.

And that just won’t do.

I stoop, gather everything, and clean it off before walking back inside.

I quietly close my bedroom door and begin parsing my collections. Every last toy is packed into spare containers with little fanfare. In one box, Micro Machines and Matchbox Cars. Lincoln Logs and Tinker Toys in another. All plastic animals in an old laundry basket. Pound Puppies, a Cabbage Patch kid, a generic Teddy Ruxpin, and a Care Bear stuffed into garbage bags.

With almost frightening speed and tact, I strip any semblance of a kid’s room from my walls, leaving an empty shell with former toys’ dusty outlines.

Mom passes by. Then walks back, looking perplexed.

“What’re you up to?”

“Just packing.”

I toss my Pog collection into a plastic bag, and shove it into a box.

She hesitates momentarily, then walks on.

***

Memories like these resurface as I run my hands along the mounds of stuff.

Laura’s creepy dolls remind me of the haunted houses we’d construct for one another, playing the lead character in our self-directed horror movies.

A broken Easter bunny candy dish summons the day Mom screeched, “You break everything I love!” after Dad propped his feet on the living room coffee table and broke off the bunny’s ears.

And then there’s the column Laura and I had given Mom for Mother’s Day, which we broke that morning while she and Dad prepped for a celebratory lunch at Golden Corral. The reddish wood glue we’d glopped onto the broken pieces seeped out of the cracks, and the column chunks thuded to the floor just as Mom came into the room to tell us it was time to go. She looked from us, to the column, then shook her head.

After that, even I couldn’t finish my imitation seafood salad.

I notice an object I’d previously dubbed “Santa Javelin” in the “maybe” pile. During the initial sort, Dad offered to chuck it out the back door like an Olympic disc-thrower.

“How far do you think I can launch this thing? To there?” he’d pointed, past the mud hole, toward our backyard pet cemetery.

Sensing her beloved decoration’s imminent demise, Mom ran from the living room, grabbed it, and reaffirmed, “It’s dual-purpose, though!”

Then proceeded to flip the pencil-shaped figure front-to-back, showing the Christmas Santa painted on one side, a Halloween witch on the other.

I failed to see the significance.

“But it’s fugly.”

“What’s ‘fugly‘?”

“Nevermind.”

***

Every little thing teems with memories, and we watch strangers cart each one off to new lives, to make new memories.

***

By the time I’ve filled the trunk with childhood relics, I’ve passed through multiple life stages–remembered the conflicts, the tears, the joys, the changes. And as I drive my trunk-o-childhood back to North Carolina, I reflect on how “home” destabilizes and reforms throughout life.

How it’s contorted by experience and embodied by the people we love.

So as I shift the trunk into the guest bedroom, I peruse its contents one more time, removing the Matchbox cars I’d so loved. The same ones I’d wheeled along my cheek as a tired toddler, my eyes growing heavier and heavier with every roll. The ones I’d returned to time and time again to escape into a world of fantasy.

I empty them onto the dining room table, carefully select the choicest ones, and pile them inside a massive vase, up to the rim.

But before I top the pile with one of my favorites, I thumb the green Mustang across the tabletop, listening to its metallic wheels squeak, filling the room with a nostalgic echo.

And I quietly hum.

Vrrrrooom!

I loved this piece. Pogs! When I returned home for Christmas during my first year of college, I realized my mother had my entire room packed for me. Yay. It’s actually very cool that you remember the end to your childhood. Mine is all very fuzzy. But maybe, like you (and many, many others), this is all just a facade anyway.

Haha! I’ve always been very definite about ending things. I’m still trying to figure out if that’s a desirable trait or not

Loved this post. I wish I could remember the end of playing with toys as clearly as you can.

Of course, what you don’t know is that Andy still has a Klingon Bird of Prey and an Enterprise-D (and a Romulan War Bird, I believe) stashed away at my parents’ house. Along with a metric ton of Playmobil. See, you never have to grow up!

HAHA! He’s told me about the toys still stashed with your parents, and how we’re going to “have to find room” to accommodate them. It’ll be interesting!